Should Preclearance Requirements & Judicial Review of Election Reforms Under the Voting Rights Act Be Strengthened? (H.R. 4)

Do you support or oppose this bill?

What is H.R. 4?

(Updated January 18, 2022)

This bill — the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2021 — would seek to restore the Voting Rights Act of 1965 after the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder ruling, which struck down one of the VRA’s key provisions. It would aim to accomplish that through the establishment of new criteria for requiring preclearance of changes to voting practices in states and political subdivisions of states, modernization of the VRA’s formula for determining which states and localities have a pattern of discrimination, and the establishment of procedures to ensure that last-minute voting changes and unequal enforcement of voting laws do not disproprotionately affect specific groups of voters.

Vote Dilution, Denial, and Abridgement

This bill would apply scrutiny to states’ and political subdivisions’ voting policies. It would also establish a definition for “vote dilution” (which would describe the systematic disempowerment of specific groups by the drawing of voting districts which dilute their voting power) and establish a judicial response to such incidents.

Violations Triggering Authority of Court to Retain Jurisdiction

This bill would also lay out 14th or 15th Amendment violations which would warrant the courts involvement in ensuring fair voting districts and practices. It would also make states which have committed 15 or more voting voting rights violations within the previous 25 calendar years; have committed ten or more voting rights violations over the previous 25 years, with at least one of which was committed by the state itself (as opposed to a political subdivision within the state); or self-administer elections and have had three or more voting rights violations within the past 25 years subject to judicial oversight.

Additionally, a political subdivision would be subject to judicial review of its voting districts and practices if three or more voting rights violations occurred in the subdivision within the previous 25 calendar years.

The Attorney General would be responsible for determining voting rights violations as early as practicable each calendar year. This would include updating the voting rights violations occurring in each state and political subdivisions from the previous calendar year.

A state or political subdivision that obtains a declaratory judgment that it has not used a voting practice to deny or abridge the right to vote would be exempt from preclearance.

Furthermore, this bill would specify that certain practices that are known to be discriminatory must be precleared before any jurisdictions implement them. These policies would include the creation of at-large districts which seem to contain disproportionately large numbers of minorities or Native Americans, conversion of single-member districts into at-large seats, changes to jurisdiction boundaries, redistricting that significantly changes a district’s minority makeup, changes in documentation or qualifications to vote, changes to multilingual voting material provision, changes to or reductions in polling places, and new list maintenance processes.

The bill would also expand the circumstances under which a court may retain the authority to preclear voting changes made by a state or political subdivision, or the Dept. of Justice (DOJ) may assign election observers to enforce the guarantees of the 14th or 15th Amendments or any other federal law protecting U.S. citizens’ right to vote.

Transparency Regarding Changes to Protect Voting Rights

This bill would also require states and political subdivisions to notify the public of changes to voting practices. The public would need to be notified of any change that would lead to different qualifications, prerequisites, standards, practices, or procedures.

Additionally, in order to identify any changes that might impact individuals’ rights to vote, states or political subdivisions would be required to provide reasonable public notice (both in physical locations within their boundaries and on their websites) detailing information on their polling places. These notices would include information such as the polling location name and number, polling location street address, information on accessibility for persons with disabilities, the voting-age population of the area served by the precinct or polling place broken down by demographic group (if such information is reasonably available), the number of registered voters assigned to the precinct or polling place broken down by demographic group (if such information is reasonably available), the number of voting machines assigned, number of voting machines accessible to persons with disabilities who are eligible to vote, number of official paid poll workers assigned, number of official volunteer poll workers assigned, and dates and hours of operation.

Transparency of Changes Relating to Demographics and Electoral Districts

This bill would require states and political subdivisions to provide reasonable public notice, in both physical locations within their boundaries and on their websites, of making any changes in the constituency that will participate in an election for federal, state, or local office or the boundaries of a voting unit or electoral district in an election for federal, state, or local office. In their notice, the state or political subdivision would be required to provide demographic and electoral data on the geographic area affected.

Compliance with this section of the bill would be voluntary for smaller political subdivisions of states, unless the subdivision is one of the following: a county or parish; a municipality with a population exceeding 10,000, as determined by the Bureau of the Census under the most recent decennial census; or a school district with a population exceeding 10,000, as determined by the Bureau of the Census under the most recent decennial census.

If a state or political subdivision fails to comply with the reporting and notice requirements in this section of the bill, no one in their boundaries’ right to vote shall be denied or abridged for failure to comply with the changes made.

Authority to Assign Observers

This bill would clarify that the Attorney General deems the assignment of observers necessary to enforce the guarantees of the 14th and 15th Amendments. It would also provide for the Attorney General to assign observers to a political subdivision if either 1) the Attorney General receives written meritorious complaints from residents, elected officials, or civic participation organizations that efforts to violate voting rights are likely to occur or 2) the Attorney General judges that observers are necessary to protect voting rights.

Further, this bill would transfer authority over observers from the United States Civil Service Commission to the Attorney General. The Attorney General would be responsible for assigning as many observers for each subdivision as they deem necessary and paying the observers. Should an observer be terminated, the Attorney General would need to be notified.

Clarification of Authority to Seek Relief

This bill would clarify that either an aggrieved (affected) person or the Attorney General may initiate action against poll taxes. Similarly, both aggrieved persons and the Attorney General could initiate actions against violations of citizens’ rights to vote under the 14th, 15th, 19th, 24th, or 26th Amendments or actions that violate citizens’ rights to vote under this legislation or any other federal law prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race, color, or membership in a language minority group in the voting process. Likewise, either an aggrieved (affected) person or the Attorney General may initiate action to enforce the 26th Amendment.

Further, this bill would clarify that the Attorney General can take action in U.S. district courts “whenever there are reasonable grounds to believe that a state or political subdivision has engaged in or is about to engage in” voting rights violations.

Preventive Relief

This bill would clarify that courts may grant preventive relief if they determine that a complainant has raised a question as to whether the challenged voting qualification or prerequisite to voting violates this bill or the Constitution and the courts determine that on balance, the hardship imposed on the defendant by grant of the relief would be less than the hardship that would be imposed on the plaintiff if relief were not granted.

Relief for Violations of Voting Rights Laws

This bill would provide for equitable relief of voting rights violations. It also directs the courts to give substantial weight to the public’s interest in expanding the right to vote when determining whether to grant, deny, stay, or vacate any order of equitable relief. Further, it would clarify that a state’s generalized interest in enforcing its enacted laws is not a relevant consideration in determining whether equitable relief is warranted.

Additionally, this bill would set forth the expectation that proximity to an election will not be presumed to constitute a harm to the public interest or a burden to the party opposing relief. It would also clarify that in reviewing an application for a stay or vacatur of equitable relief granted under this bill, the courts should give substantial weight to the reliance interests of citizens who acted pursuant to the order under review.

Enforcement of Voting Rights by Attorney General

This bill would authorize the Attorney General, before commencing a civil action, to issue a demand for inspection and information in writing to any state or political subdivision. It also outlines requirements for a demand by the Attorney General and responses that states and political subdivisions are required to provide in response to a demand by the Attorney General.

Grants to Assist with Notice Requirements Under the Voting Rights Act of 1965

Finally, this bill would empower the Attorney General to make annual grants to small jurisdictions (populations under 10,000) that submit applications for help complying with the requirements of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Argument in favor

The Supreme Court’s decisions in Shelby County and Brnovich have severely weakened the Voting Rights Act (VRA), which up until then had been the key protection ensuring that everyone — particularly minorities — gets the same access to the ballot box. This bill would help to ensure that states with a history of voter suppression don’t take steps to restrict voting access in future elections, thereby increasing the American public’s confidence that elections are fairly administered.

Argument opposed

The Supreme Court’s decisions in Shelby County and Brnovich were properly decided, as the Court ruled that the VRA’s requirements were no longer needed given changes to the law and the U.S. itself since the VRA’s enactment in 1965, and that things like bans on voting in the wrong precinct or ballot harvesting aren’t discriminatory. This bill would unnecessarily politicize election administration and give the federal government too much control over a state-level issue, potentially undermining confidence in elections.

Impact

Voters; election districts; election officials; states’ political subdivisions; states; elections; and voter protections.

Cost of H.R. 4

A CBO cost estimate is unavailable.

Additional Info

In-Depth: Sponsoring Rep. Terri Sewell (D-AL) reintroduced this bill from the 116th Congress to protect voting rights:

“The right to vote is the most sacred and fundamental right we enjoy as American citizens and one that the Foot Soldiers fought, bled, and died for in my hometown of Selma, Alabama. Today, old battles have become new again as we face the most pernicious assault on the right to vote in generations. It’s clear: federal oversight is urgently needed. With the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, we’re standing up and fighting back. By preventing states with a recent history of voter discrimination from restricting the right to vote, this bill restores the full promise of our democracy and advances the legacy of those brave Foot Soldiers like John Lewis who dedicated their lives for the sacred right to vote. I’m proud to be introducing this bill today and look forward to its swift passage. Our democracy is at stake.”

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) supports this bill:

“The House today is taking a momentous step to secure the sacred right to vote for generations to come. With the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, proudly introduced today by Congresswoman Terri Sewell alongside Judiciary Committee Chairman Jerry Nadler, Democrats are fighting back against an anti-democratic tide, protecting access to the ballot box for every American and carrying on the cause to which our beloved John Lewis devoted his entire life. When the House returns on August 23rd, Democrats plan to pass H.R. 4 – and we hope it can secure the bipartisan support this vital legislation deserves.”

In their minority views to this bill’s committee report in the 116th Congress, House Judiciary Committee Republicans argued that this bill would give the DOJ and Attorney General too much power; politicize the process of setting election procedures; and punish all political subdivisions within a state for a single political subdivision’s misbehavior. They also argued that existing law is sufficient to protect voters’ rights and that this bill isn’t constitutional:

“Existing law already protects Americans from voting discrimination: Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act allows lawsuits, even those based on disparate impacts, to stop [s]tate and local voting laws, including through preliminary injunctions; and Section 3 of the Voting Rights Act allows federal judges across the country to put jurisdictions under preclearance requirements when those jurisdictions have a record of actual discrimination in voting. In sum, [this bill] unconstitutionally creates a system in which a politicized Department of Justice can federalize control over [s]tate and local elections when there is no evidence the [s]tate or locality engaged in actual discriminatory conduct.”

During the 116th Congress, Rep. Mike Johnson (R-LA) argued that while discriminatory voting restrictions are wrong, this bill would prohibit states from enforcing even neutral voting laws, thereby “unconstitutionally deny[ing] states and localities control” of elections regardless of whether those laws are discriminatory. Johnson — like many Republicans — specifically criticized this bill’s automatic requirement that voter ID laws be precleared, calling it “federal fiat.” Finally, he argued that the DOJ has a “history of politicizing” preclearance, which has allowed it to amend or veto state laws to benefit whichever party is in power.

This legislation has 218 Democratic House cosponsors in the 117th Congress. In the 116th Congress, this legislation passed the House by a 228-187 vote on October 23, 2019 with the support of 229 Democratic House cosponsors. Its Senate companion, sponsored by Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT), had 47 Senate cosponsors, including 44 Democrats, two Independents, and one Republican, and didn’t receive a committee vote.

Senate Republicans aren’t expected to move on this legislation, in part because of the provision requiring automatic preclearance of voter ID laws. In an indication of Republicans’ opposition to this legislation, Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner (R-WI) — who sponsored the last VRA reauthorization in 2006 and has introduced alternate legislation, the Voting Rights Amendment Act of 2019 (H.R.1799) to amend the VRA without some of this legislation’s provisions — calls this legislation a “poison pill” that “won’t go anywhere in the Senate.”

A range of civil rights and voters’ advocacy groups, including the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights; Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law; Brennan Center for Justice; Human Rights Campaign (HRC); National Urban League; Asian Americans Advancing Justice (AAJC); National Association of Latino Elected Officials (NALEO) Educational Fund; Native American Rights Fund (NARF); National Education Association (NEA); Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF); NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., support this legislation.

Last Congress, this legislation had 193 Democratic House cosponsors. Its Senate companion, sponsored by Sen. Leahy, had 49 Senate cosponsors, including 46 Democrats, one Republican, and two Independents. Neither bill received a committee vote.

Of Note: The Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder struck down Section 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965, which outlined the qualifications needed to determine which states are required by the Justice Department to preclear elections changes in states with a history of voter discrimination.

In their ruling, the majority said the formula used in Section 4 of the VRA imposed extraordinary burdens on state and local governments based on outdated conditions. Part of Chief Justice John Roberts’ rationale in the majority opinion was that the law has so dramatically changed circumstances that preclearance, at least under the decades-old formula, was no longer appropriate.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who dissented, said that “throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

Since the Shelby decision, nearly 24 states have implemented restrictive voter ID laws; and previously-covered states have closed or consolidated polling places, shortened early voting, and imposed other measures that restrict voting. During the 2018 election, voters of color across the U.S. complained of unusual barriers to voting ahead of Election Day, including:

An “exact match” voter ID rule requiring the information on a government-issued ID card like a driver’s license or Social Security card to match up exactly with the name and information on a voter registration application, down to hyphens and typos in Georgia, where Secretary of State Brian Kemp administered the state’s election while running against Democrat Stacey Abrams for governor (Kemp ultimately won in a tight victory). This led to 53,000 names being purged from the voting rolls due to a mismatch between the voter rolls and their ID cards.

A voter ID law forcing voters to produce a street address (which those living on Native American reservations aren’t required to have) in North Dakota, which sent Native voters into a scramble to provide street addresses and ran the risk of disenfranchising an entire group of minority voters.

Other legal challenges about restrictive voter ID laws also cropped up in New Hampshire, Missouri, Florida, and North Carolina.

Rep. Sewell claimed without evidence that voter suppression in Georgia changed the outcome of the state’s governor’s race:

“Stacey Abrams is not governor of Georgia today because of voter suppression that took place in that state. The Republicans have realized that when you limit access to certain populations and they don’t vote, you have a better chance of winning. That’s the bottom line.”

In September 2018, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (USCCR) released a report examining the state of voting rights in the U.S. It found that in states across the country — and especially in states previously covered by the VRA — voter suppression tactics are trampling minority rights. Due to its findings, the Commission unanimously called on Congress to restore and expand voter protections in the VRA.

On July 1, 2021, the Supreme Court’s decision in Brnovich v. DNC upheld Arizona’s voting laws that prohibited the use of “ballot harvesting” — the practice of third parties collecting voters’ ballots — and requiring that voters at the wrong precinct either go to the proper precinct to vote or cast a provisional ballot if it’s too late for them to make it to their precinct. Democrats had challenged those rules and alleged that they were discriminatory under the VRA, which the Supreme Court rejected.

While congressional rebuke of Supreme Court decisions via legislation isn’t unheard of, the pace at which Congress has chosen to override Supreme Court rulings has slowed down in recent years, largely to the polarization of the U.S. political system (both houses of Congress need to come to a bipartisan consensus for a statutory override). However, William & Mary law professor Neal Devins notes, “Some of the most notable overrides include protections of minority interests such as voting, religious minorities, and woman in the Title VII employment discrimination context.” For example, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act and the Religious Freedom Restoration Act were both born out of a desire to upend unpopular high court decisions.

Media:

Sponsoring Rep. Terri Sewell (D-AL) Press Release (117th Congress)

Sponsoring Rep. Terri Sewell (D-AL) Press Release (116th Congress)

House Judiciary Committee Press Release (116th Congress)

House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer (D-MD) November 8, 2019 Dear Colleague Letter (116th Congress)

Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF) (In Favor)

Causes (116th Congress Version)

Summary by Lorelei Yang

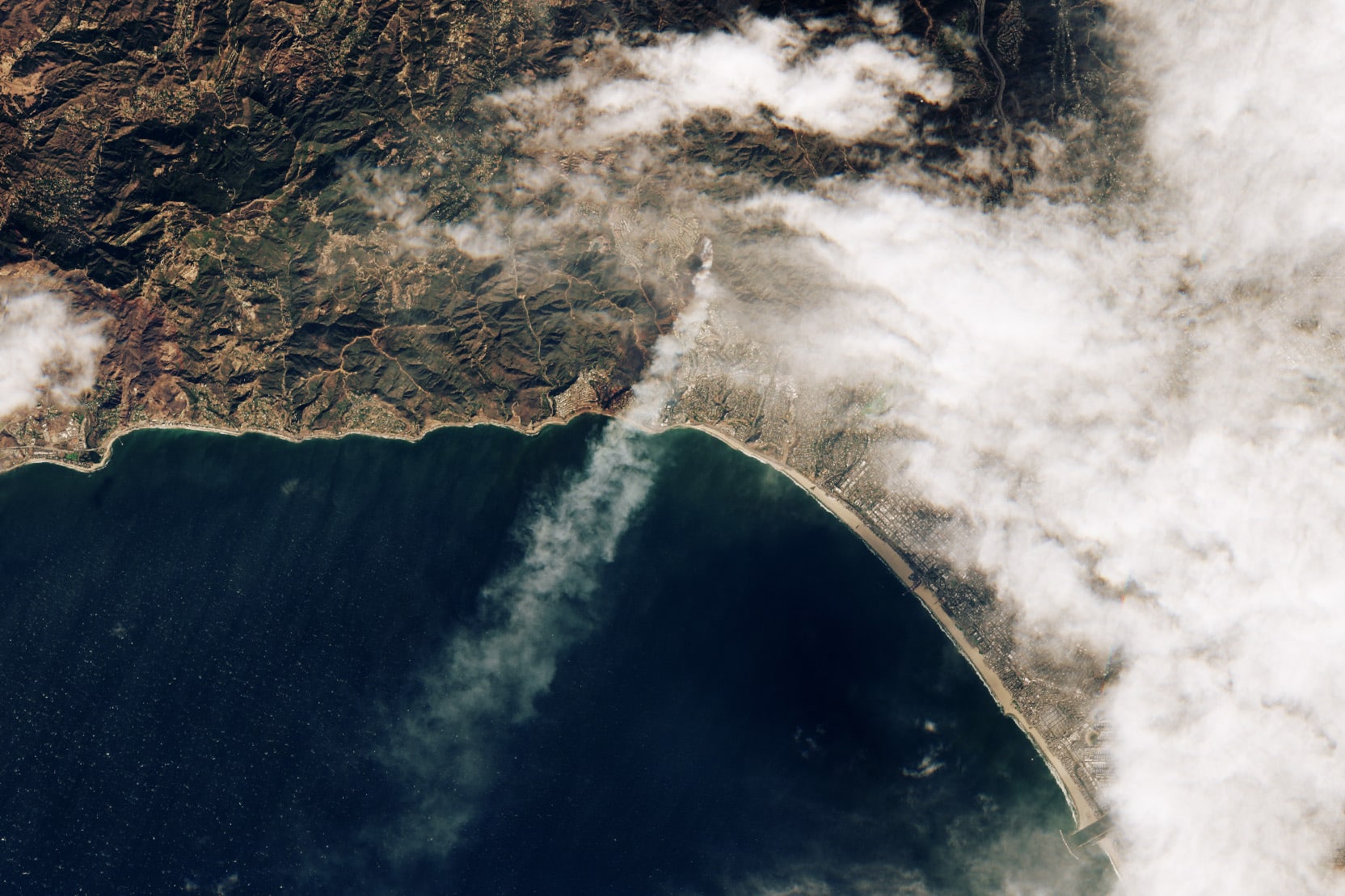

(Photo Credit: iStockphoto.com / adamkaz)

The Latest

-

Changes are almost here!It's almost time for Causes bold new look—and a bigger mission. We’ve reimagined the experience to better connect people with read more...

Changes are almost here!It's almost time for Causes bold new look—and a bigger mission. We’ve reimagined the experience to better connect people with read more... -

The Long Arc: Taking Action in Times of Change“Change does not roll in on the wheels of inevitability, but comes through continuous struggle.” Martin Luther King Jr. Today in read more... Advocacy

The Long Arc: Taking Action in Times of Change“Change does not roll in on the wheels of inevitability, but comes through continuous struggle.” Martin Luther King Jr. Today in read more... Advocacy -

Thousands Displaced as Climate Change Fuels Wildfire Catastrophe in Los AngelesIt's been a week of unprecedented destruction in Los Angeles. So far the Palisades, Eaton and other fires have burned 35,000 read more... Environment

Thousands Displaced as Climate Change Fuels Wildfire Catastrophe in Los AngelesIt's been a week of unprecedented destruction in Los Angeles. So far the Palisades, Eaton and other fires have burned 35,000 read more... Environment -

Puberty, Privacy, and PolicyOn December 11, the Montana Supreme Court temporarily blocked SB99 , a law that sought to ban gender-affirming care for read more... Families

Puberty, Privacy, and PolicyOn December 11, the Montana Supreme Court temporarily blocked SB99 , a law that sought to ban gender-affirming care for read more... Families

Climate & Consumption

Climate & Consumption

Health & Hunger

Health & Hunger

Politics & Policy

Politics & Policy

Safety & Security

Safety & Security