Should More Police Officers Have Body Cameras? (H.R. 1680)

Do you support or oppose this bill?

What is H.R. 1680?

(Updated June 5, 2020)

Video Summary:

This bill would establish a grant program to give state and local law enforcement agencies money to buy body cameras for all on-duty police officers. The hope is that these body cameras would improve evidence collection, deter excessive force, and improve both police accountability and transparency.

These programs would operate on the assumption that officers wearing body cameras should minimize recording of data that’s unrelated to law enforcement activities. Officers would also be held accountable for explaining when they don't record activities and situations that should’ve been recorded. Officers would also have to get consent from witnesses and crime victims before recording. Members of the public would be able to file complaints related to the improper use of body cameras.

At the end of the day, these body camera programs would be operating to collect more data from state and local law enforcement agencies on:

Incidents when officers use force — broken down by the race, ethnicity, gender, and age of the person who was the target of force.

The number of complaints filed against law enforcement officers, and the nature of those complaints.

How camera footage is used for evidence collection when investigating crimes.

Argument in favor

Body cameras will help with evidence collection in addition to reducing the use of excessive force by police officers. It’s a positive for both the general public and for law enforcement officials.

Argument opposed

Body cameras threaten the privacy of citizens and police officers — especially because there are no standard regulations (at the local or federal level) for how the camera data is stored, used, or destroyed.

Impact

The general public, law enforcement officers, law enforcement agencies at the state and local level, the Office of Justice Programs, body camera manufacturers, and the Assistant Attorney General.

Cost of H.R. 1680

A CBO cost estimate is unavailable.

Additional Info

In-Depth:

Grants awarded through this program would last for two years, with 50 percent of the grant money being handed out right when it's awarded. The remaining 50 percent would be distributed only the law enforcement agency has established policies and guidelines for using the cameras, storing and destroying the data they gather, how to release stored data, and shared the new policies with the public.

The system that stores the data from the body cameras would log all viewing, modification, or deletion of stored data in order to prevent unauthorized access or disclosure of stored data. Law enforcement officers would be prohibited from accessing the system without authorization.

Data gathered through the body cameras in these programs would only be used for collecting crime-related evidence, investigating misconduct, and for some training purposes. The transfer of data to another law enforcement or intelligence agency would be prohibited, except for:

Criminal investigations where there is reasonable suspicion that the requested data contains evidence related to that investigation.

Civil rights claims investigating any right, privilege, or immunity that is protected by the Constitution or laws of the U.S.

Applications would be made to the Assistant Attorney General by the chief executive of a state, local government, or Indian tribe. Within 90 days of this bill’s enactment the Assistant Attorney General would release the requirements of the grant application process.

Within two years of grants being disbursed, the Assistant Attorney General would conduct a study on the impact of body cameras on the use of force by police officers, on public safety, storage issues, and best practices. This study would be sent to Congress within 180 days of its completion.

Of Note:

Body cameras have been at the center of police accountability debates, long before Michael Brown and Eric Garner were household names. The police shooting of Walter Scott in April 2015 again turned national attention to the question, "Are body cameras the answer to avoiding excessive, and sometimes fatal, police force?" As the National Journal explains:

"Michael Slager, the police officer who killed Walter Scott [in] North Charleston, wasn't wearing a body camera. But video shot by a bystander showed Slager shooting Scott eight times in the back as he was running away, leading to murder charges for the officer on Tuesday. Without that footage, advocates say, the outcome of the deadly encounter would've been different.

"," said Democratic Rep. Emanuel Cleaver of Missouri, who's introduced legislation supporting police body cameras. The case for police officers to wear them ".""

A similar version of this bill was introduced in December 2014, but it failed to get out of committee before the end of the 113th Congress.

Media:

Sponsoring Rep. Corrine Brown (D-FL) Press Release

ACLU (In Favor)

California Magazine (Context)

Office of Justice Programs (Context)

Wall Street Journal (Context)

LA Times (Context)

The Latest

-

IT: Trump's 2016 'deny, deny, deny' campaign strategy, and... How can you help the civilians of Ukraine?Welcome to Wednesday, May 8th, weekenders... As Trump's hush money trial enters it's third week, the 2016 campaign strategy of read more...

IT: Trump's 2016 'deny, deny, deny' campaign strategy, and... How can you help the civilians of Ukraine?Welcome to Wednesday, May 8th, weekenders... As Trump's hush money trial enters it's third week, the 2016 campaign strategy of read more... -

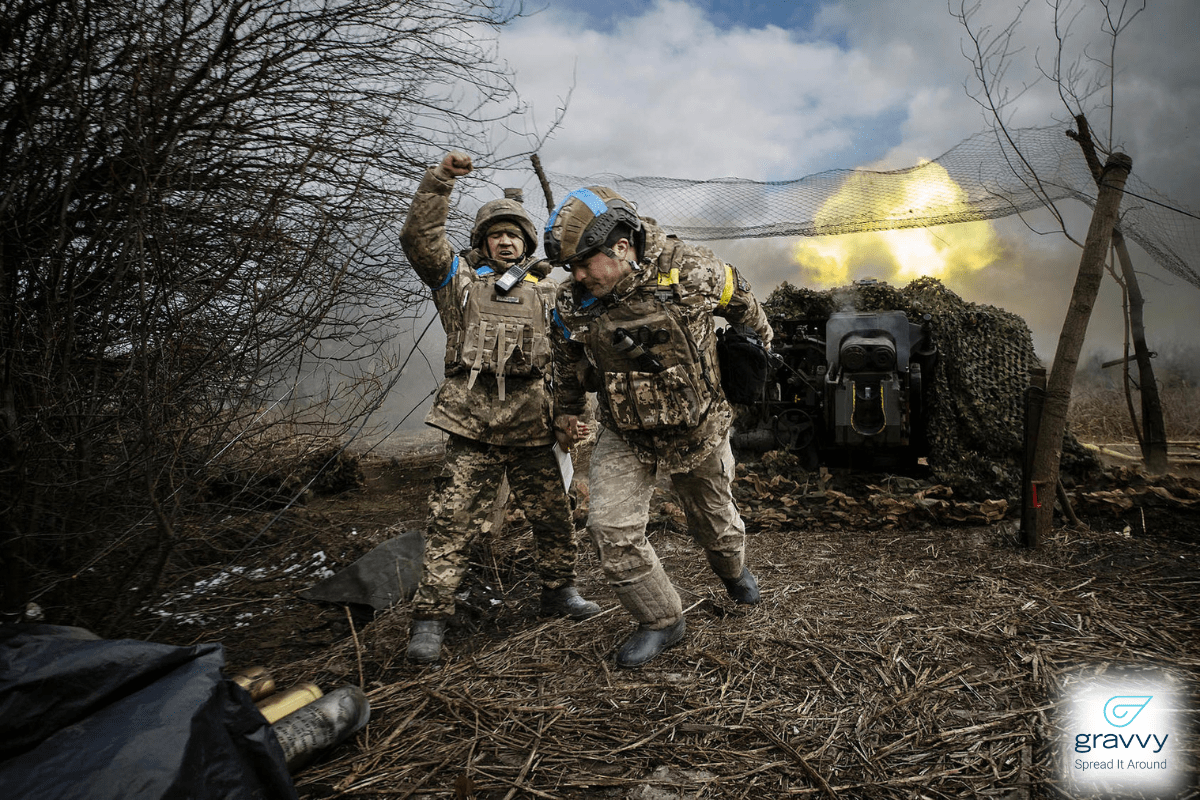

How To Help Civilians in UkraineHeavy shelling and fighting have caused widespread death, destruction of homes and businesses, and severely damaged read more... Public Safety

How To Help Civilians in UkraineHeavy shelling and fighting have caused widespread death, destruction of homes and businesses, and severely damaged read more... Public Safety -

The Latest: Israel Evacuates Rafah, Palestinian Place of RefugeUpdated May 6, 2024, 12:00 p.m. EST The Israeli military is telling residents of Gaza who have sought shelter in Rafah to read more... Israel

The Latest: Israel Evacuates Rafah, Palestinian Place of RefugeUpdated May 6, 2024, 12:00 p.m. EST The Israeli military is telling residents of Gaza who have sought shelter in Rafah to read more... Israel -

Trump Hush Money Trial Enters Third Week, Strategy to ‘Deny, Deny, Deny’Updated May 6, 2024, 11:00 a.m. EST The criminal trial to determine whether Trump is guilty of falsifying records to cover up a read more... Law Enforcement

Trump Hush Money Trial Enters Third Week, Strategy to ‘Deny, Deny, Deny’Updated May 6, 2024, 11:00 a.m. EST The criminal trial to determine whether Trump is guilty of falsifying records to cover up a read more... Law Enforcement

Climate & Consumption

Climate & Consumption

Health & Hunger

Health & Hunger

Politics & Policy

Politics & Policy

Safety & Security

Safety & Security