Should Congress Eliminate the Deadline for Ratifying the Equal Rights Amendment? (H. Joint Res. 79)

Do you support or oppose this bill?

What is H. Joint Res. 79?

(Updated December 18, 2020)

This resolution would eliminate the deadline Congress imposed on the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which would prohibit discrimination on the basis of sex under the U.S. Constitution. This bill’s enactment would negate the deadline Congress imposed when it initially passed the ERA and later extended, effectively allowing the ERA to take effect once it’s ratified by three-fourths of the states.

The ERA was passed by Congress in 1972 and provided states a seven-year time limit to ratify the amendment, which was then extended to 1982 after six years had elapsed. Once the 1982 deadline arrived, the ERA had been ratified by 35 states — three short of the requirement. Following its failure to achieve ratification before the 1982 deadline, the ERA was reintroduced in Congress by those who believed the ratification process would have to begin anew.

However, there are some — including the sponsor of this legislation — who believe that to be unnecessary. Time limits on constitutional amendments hadn’t been utilized prior to the 18th Amendment, so ratification time limits are a self-imposed constraint rather than a constitutional requirement. As a case in point, the 27th Amendment (also known as the Madison Amendment) wasn’t ratified until nearly 203 years after Congress passed it and it sent it to the states.

Argument in favor

It makes no sense for the Equal Rights Act ratification process to start fresh after 37 states have already expressed their approval for it. This is especially true in light of the fact that other Constitutional amendments — most notably the 27th Amendment — have been allowed to pass long after their first proposal. The ERA would provide important protections for women’s rights and equality, and should be ratified as soon as possible, now that Virginia’s state legislature has committed to taking it up in January 2020.

Argument opposed

When Congress self-imposes a time limit on the ratification of a constitutional amendment they need to stick to it, even if it means the process has to begin anew because it wasn't ratified on time. The ERA could potentially regain the support it had once the process restarts. More broadly, there could be unwanted unintended consequences of ERA ratification, such as forcing women into the draft, eliminating single-sex bathrooms, or weakening restrictions on abortion.

Impact

Women; women’s equality; women and men who face discrimination on the basis of sex; lawmakers and citizens who would otherwise have to begin the ERA ratification process anew; Equal Rights Act (ERA); ERA ratification; state legislatures; Virginia; and Congress.

Cost of H. Joint Res. 79

A CBO cost estimate is unavailable.

Additional Info

In-Depth: Sponsoring Rep. Jackie Speier (D-CA), co-chair of the Democratic Women’s Caucus, reintroduced this resolution from the 115th Congress to eliminate the ratification deadline for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). When she introduced this resolution in the 115th Congress, Rep. Speier said:

“When asked, 96% of Americans think that women and men should have equal rights, and 88% believe that our Constitution should affirm those rights, while 72% of Americans mistakenly believe the Constitution already includes such a guarantee. Given the current political climate, and the overwhelming support, it’s clear that the ERA is still a necessity. As the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia explained in a Supreme Court opinion, ‘Certainly the Constitution does not require discrimination on the basis of sex. The only issue is whether it prohibits it. It doesn’t.’ Women, and men, in America are faced with a Congress and state legislators who are focused like a laser on attacking women’s health. We have a new Supreme Court Justice and, as such, many questions about issues of gender equality hanging in the balance. The President’s ongoing executive actions threatening to rollback back all of our hard-won rights, including his reinstatement and expansion of the Global Gag Rule on the day after the 44th anniversary of Roe v. Wade, make ratification of the ERA more important than ever.”

At this resolution’s committee markup, Rep. Nadler expressed support in his opening statement:

“[T]his short and straightforward measure provides that notwithstanding the ratification deadline that Congress set for the ERA in 1972, and extended in 1978, the ERA "shall be valid to all intents and purposes as part of the Constitution whenever ratified by the legislatures of three-fourths of the several states. I would hope that there is little dispute about the need for enshrining in the Constitution a clear and firm statement guaranteeing equal rights under the law regardless of sex… Some may argue that we do not need an ERA, or that Congress cannot change the deadline for ratification retroactively. But both arguments are clearly wrong. As a straightforward moral matter, our Constitution should explicitly guarantee equality of rights under the law regardless of sex. Moreover, while the Constitution has been interpreted to provide a considerable level of protection against sex discrimination already, those interpretations can always change for the worse. The ERA would secure and potentially enhance these existing protections… Adopting the ERA would bring our country closer to truly fulfilling our values of inclusion and equal opportunity for all people. Adopting this legislation would help make this a reality.”

Rep. Nadler also defended Congress’ ability to remove the deadline for ERA ratification, reasoning:

“As to Congress’s authority to change or eliminate the ratification deadline, Article V of the Constitution, which governs the constitutional amendment process, does not provide for a ratification deadline of any kind. Article V also contemplates that Congress alone is responsible for managing the constitutional amendment process, given that it assigns only to Congress an explicit role in the amendment process and does not mention any role for the Executive or Judicial Branches. The Supreme Court made clear in Coleman v. Miller that Article V contains no implied limitation period for ratifications and that Congress may choose to determine ‘what constitutes a reasonable time and determine accordingly the validity of ratifications’ because such questions are ‘essentially political.’ The Court concluded that in short, Congress ‘has the final determination of the question whether by lapse of time its proposal of [an] amendment ha[s] lost its vitality prior to the required ratifications.’ Similarly, when this Committee considered an extension of the ratification deadline in 1978, it concluded that ‘rescissions [of ratifications] are to be disregarded’ based on the generally-agreed view of constitutional experts that ‘the decision as to whether rescissions are to be counted is a decision solely for the Congress sitting at the time the 38th State has ratified, as part of its decision whether an amendment has been validly ratified.’”

After the November elections in Virginia, which saw Democrats gain control of the state’s legislature (thereby increasing the odds of Virginia becoming the 38th state and final state needed to ratify the ERA), Rep. Nadler said the need for this resolution is even greater than before:

“The ERA would affirm and strengthen the rights of women in our Constitution. Congress created this deadline and, it is clear, Congress has every authority to remove it now. After decades of work by tireless advocates, it is time for Congress to act and clear the way for Virginia, or any other state, to finally ratify the ERA and for discrimination on the basis of sex to be forever barred by the Constitution.”

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg supports the goals of the ERA, but believes that because the time limit imposed on its ratification by Congress elapsed, its ratification will have to restart from the beginning before it can become part of the Constitution:

"I was a supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment. I hope someday it will be put back in the political hopper and we'll be starting all over again collecting the necessary states to ratify it."

ERA opponents worry that it would upset traditional gender roles, fortify the Supreme Court’s ruling in Roe v. Wade, and provoke unintended consequences (such as incidentally prohibiting sex-segregated bathrooms). In a September 2016 article for Bloomberg Opinion, conservative columnist Ramesh Ponnuru wrote:

“If the military draft ever returned, the [ERA] would mean that women had to be subject to it. Supporters of the right to abortion that the Supreme Court had pretended to find in the Constitution would use the ERA to strengthen their case, too.”

Some ERA opponents also point out that five states (Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Tennessee) that previously ratified the ERA have since rescinded their ratification. They believe that ERA ratification that counts the rescinded ratifications would be open to court challenges.

However, based on legal precedent, states’ recission of their ratifications shouldn’t matter: when some states tried to rescind their ratifications of the 14th and 15th Amendments, their original ratifications were counted anyway. Moreover, ERA supporters argue that the ERA’s deadline language is in its preamble, and isn’t part of the text that states vote on. Finally, ERA supporters point to the 1992 adoption of the Madison Amendment (which was adopted by Congress over 200 years after its initial proposal to Congress) as proof that there’s no true deadline for making Constitutional amendments.

This resolution passed the House Judiciary Committee by a 21-11 party-line vote on November 13, 2019 with the support of 216 bipartisan House cosponsors, including 215 Democrats and two Republicans. Sen. Ben Cardin’s (D-MD) identical Senate resolution (S.J.Res.6) has three Senate cosponsors, including two Republicans and one Independent.

In the 115th Congress, this resolution (H.J.Res.53) had 167 bipartisan House cosponsors, including 166 Democrats and one Republican. The identical Senate resolution (S.J.Res.5), sponsored by Sen. Cardin, had 36 Senate cosponsors, including 35 Democrats and one Independent.

Seattle Indivisible and Equality Now support this resolution in the 116th Congress. In the 115th Congress, a broad range of women’s, progressive, and feminist organizations, including 9 to 5, the American Association of University Women (AAUW), National Organization for Women (NOW), National Women's Law Center, and Women Rise Up Now, endorsed this resolution.

Of Note: The Equal Rights Amendment was written by Alice Paul, a leader of the women’s suffrage movement and women’s rights activist, in 1923. Paul rewrote the ERA to its current wording in 1943, modeling it on the language of the 19th Amendment. The final, current ERA has three provisions:

- Equality of rights under the shall not be abridged or denied by the United States or by any state on account of sex.

- Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

- This amendment shall take effect two years after the date of ratification.

The ERA passed Congress by the required two-thirds majority on March 22, 1972 and was sent to the states for ratification. However, anti-feminist leader Phyllis Schlafly mobilized a quick and extraordinarily successful movement to beat the ERA. The anti-ERA movement warned of disastrous consequences if traditional gender roles were eroded. Working together, Schlafly’s organization, Stop Taking Our Privileges (STOP) ERA and the active conservative interest group Eagle Forum warned that the ERA was too broad and that it would eliminate government distinctions between men and women. They also circulated printouts of popular Senate Judiciary Chair Sam Ervin’s invectives against the ERA and claimed that the ERA would lead to mandatory military service for women, unisex bathrooms, unrestricted abortions, women becoming Roman Catholic priests, and same-sex marriage. STOP ERA members lobbied state governments by handing out homemade bread with the slogan, “Preserve Us From a Congressional Jam; Vote Against the E.R.A. Sham.”

An original seven-year deadline was later extended by Congress to June 30, 1982. At the extended deadline’s expiration, only 35 of the necessary 38 states (three-fourths of the states need to ratify a Constitutional amendment) had ratified the ERA, so the ERA isn’t part of the Constitution.

Most recently, Illinois ratified the ERA in May 2018 — it was the 37th state to do so. After the November 2019 elections in Virginia, which gave Democrats control of the Virginia state legislature, activists are hopeful that Virginia may become the 38th state to ratify the ERA in early 2020. Virginia’s incoming Democratic leaders have promised to take the ERA up immediately when the state legislature convenes in January 2020, and since the ERA failed by the Virginia Senate by a single vote when the chamber was still under Republican control, passage is virtually guaranteed.

In accordance with the traditional ratification process outlined in Article V of the Constitution, the ERA has been reintroduced in every session of Congress since 1982. The only procedural action taken on it — a House floor vote in 1983 — failed by six votes. In the 116th Congress, the traditional ERA ratification bill is H.J.Res.35, sponsored by Reps. Carolyn Maloney (D-NY) and Tom Reed (R-NY) with the support of 178 Democratic House cosponsors (Rep. Reed is only Republican House member supporting the bill).

While women have made tremendous progress towards equality since the ERA’s deadline passed in 1982, activists argue that the statutes and case law that have produced major advances in women’s rights since the mid-20th century are vulnerable or susceptible to being ignored, weakened, or even reversed. By contrast, the ERA — as a Constitutional amendment — would be far more forceful. Activists also contend that ERA ratification would improve the United States’ global credibility with respect to sex discrimination (134 nations have constitutional provisions guaranteeing gender equality under the law).

In April 2019, the House Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights and Civil Liberties held the first official hearing on the ERA in almost 40 years.

Media:

-

Sponsoring Rep. Jackie Speier (D-CA) Press Release (115th Congress)

-

House Judiciary Committee Press Release

-

House Judiciary Committee Chairman Rep. Jerry Nadler (D-NY) Press Release Announcing Committee Markup

-

Feminist Majority Foundation

-

Ms.

-

Roll Call

-

Seattle Indivisible (In Favor)

-

Equality Now (In Favor)

-

Bloomberg Opinion (Opposed)

-

Alice Paul Institute (Context)

-

GovTrack (Context)

-

Alice Paul Institute - Equal Rights Act in the 116th Congress

-

New York Times (Context)

-

National Journal (Context)

- National Review (Context)

- National Law Journal (Context)

-

Smithsonian Magazine (Context)

-

Countable - ERA Ratification Resolution in the 116th Congress

-

Countable - Senate Version in the 115th Congress

Summary by Eric Revell and Lorelei Yang

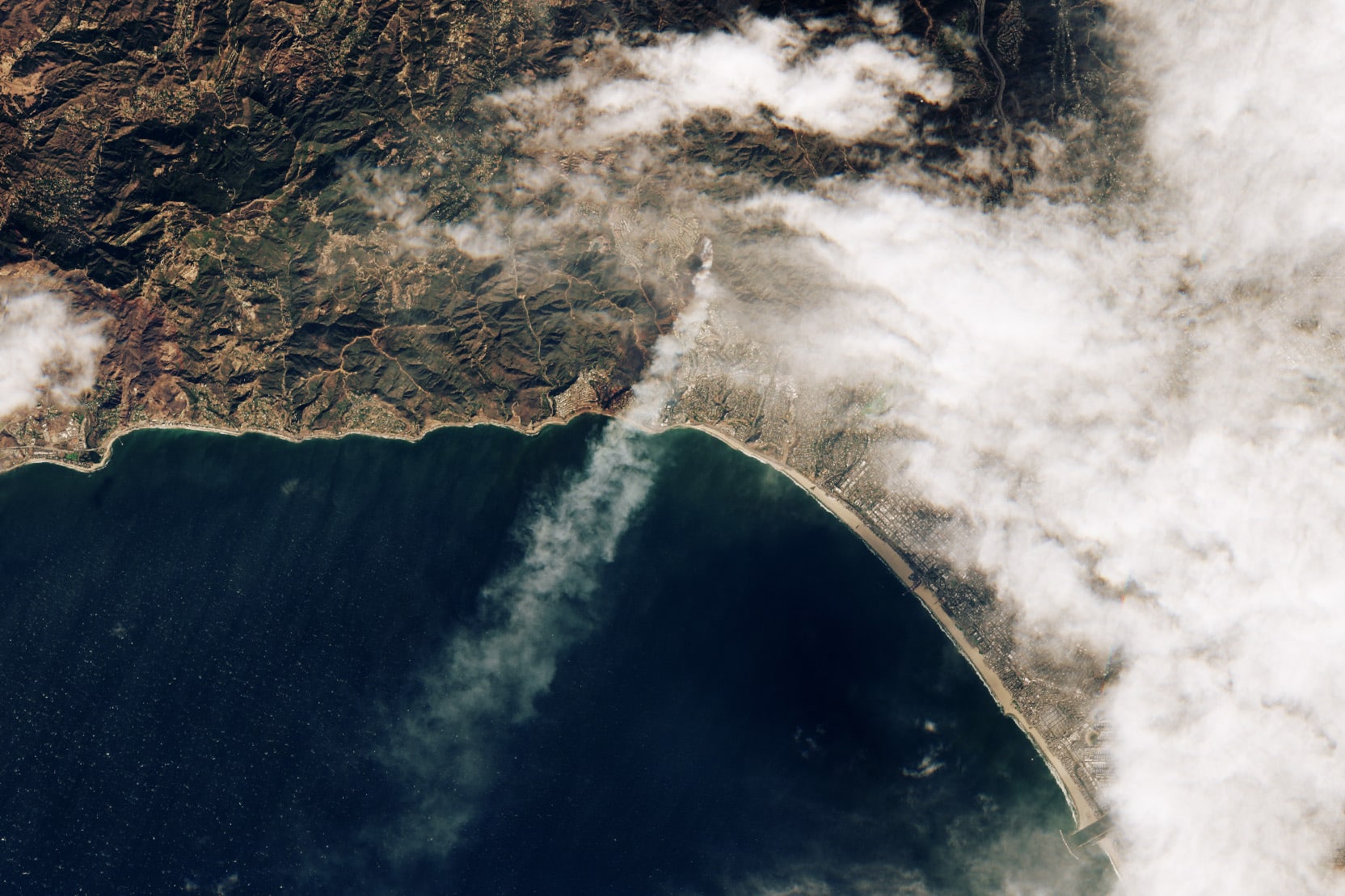

(Photo Credit: Flickr user David)The Latest

-

Changes are almost here!It's almost time for Causes bold new look—and a bigger mission. We’ve reimagined the experience to better connect people with read more...

Changes are almost here!It's almost time for Causes bold new look—and a bigger mission. We’ve reimagined the experience to better connect people with read more... -

The Long Arc: Taking Action in Times of Change“Change does not roll in on the wheels of inevitability, but comes through continuous struggle.” Martin Luther King Jr. Today in read more... Advocacy

The Long Arc: Taking Action in Times of Change“Change does not roll in on the wheels of inevitability, but comes through continuous struggle.” Martin Luther King Jr. Today in read more... Advocacy -

Thousands Displaced as Climate Change Fuels Wildfire Catastrophe in Los AngelesIt's been a week of unprecedented destruction in Los Angeles. So far the Palisades, Eaton and other fires have burned 35,000 read more... Environment

Thousands Displaced as Climate Change Fuels Wildfire Catastrophe in Los AngelesIt's been a week of unprecedented destruction in Los Angeles. So far the Palisades, Eaton and other fires have burned 35,000 read more... Environment -

Puberty, Privacy, and PolicyOn December 11, the Montana Supreme Court temporarily blocked SB99 , a law that sought to ban gender-affirming care for read more... Families

Puberty, Privacy, and PolicyOn December 11, the Montana Supreme Court temporarily blocked SB99 , a law that sought to ban gender-affirming care for read more... Families

Climate & Consumption

Climate & Consumption

Health & Hunger

Health & Hunger

Politics & Policy

Politics & Policy

Safety & Security

Safety & Security