Should Lynching be a Federal Hate Crime? (H.R. 35)

Do you support or oppose this bill?

What is H.R. 35?

(Updated November 17, 2021)

This bill — the Emmett Till Antilynching Act — would amend the U.S. Code to specify that lynching is a heinous crime that warrants an enhanced sentence under hate crimes statutes.

Argument in favor

Lynching is a horrific crime that historically has both hate- and race-based elements. Making it illegal at the federal level, and adding a hate crime enhancement, rights the historic wrong of the crime itself being allowed to continue for over a century, as well as the nearly 4,000 crimes of this nature that went largely unpunished.

Argument opposed

It has been decades since the last lynching occurred in the U.S., and the Civil Rights Act has long-since negated the need for a federal anti-lynching law. The Senate’s 2005 apology to lynching victims and their descendants suffices to right the wrong of the federal government failing to enact an anti-lynching law when the crime occurred regularly.

Impact

Federal hate crime laws; people who commit lynching; and victims of lynching.

Cost of H.R. 35

A CBO cost estimate is unavailable.

Additional Info

In-Depth: Rep. Bobby Rush (D-IL) reintroduced this bill from the 115th Congress on the opening day of the 116th Congress along with four other bills speaking to his legislative priorities for his district and the nation. Rep. Rush expressed a belief that the American people in the midterm elections “demanded a Congress that works for the people and one that will improve the lives of seniors, children, and hard-working Americans”:

“For too long, the American people have been confronted with an agenda that has harmed the futures of families and seniors, all to further enrich the wealthy and well-connected. House Democrats will deliver an ambitious, forward-looking, and positive agenda for the people.”

Bryan Stevenson, Executive Director of the Equal Justice Initiative and the founder of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, a national memorial acknowledging the victims of racial terror lynchings, argues:

“It is never too late for our nation to express our sorrow for the decades of racial terror that traumatized millions in this country. Passing an anti-lynching law is not just about who we were decades ago, it's a statement about who we are now that is relevant, important and timely."

In an NPR interview after the Senate passed a resolution apologizing to lynching victims for its failure to pass anti-lynching legislation, University of New Hampshire African-American History and American Studies professor Harvard Sitkoff argued that the need for federal anti-lynching legislation was negated by the Civil Rights Act of the 1960s:

“[L]ynching as such now has decreased very significantly. In part because of the threat of federal anti-lynching legislation, Southern states began to do much, much more to stop lynching from occurring and to themselves prosecute lynchers when a lynching did occur. To a very large extent, then, a federal anti-lynching law became superfluous.”

This bill has 128 bipartisan cosponsors, including 127 Democrats and one Republican, in the 116th Congress.

Last Congress, this bill had 68 bipartisan House cosponsors (65 Democrats and three Republicans) and didn’t receive a committee vote. Its Senate companion, introduced by Sen. Kamala Harris, passed the Senate by voice vote with the support of 39 bipartisan cosponsors (28 Democrats, nine Republicans and two Independents)

Of Note: This bill is named for Emmett Till, a 14-year-old killed in Mississippi in 1955. In 2018, the Justice Department reopened its investigation into Till’s killing. When the DOJ announced the reopening of the Till investigation, Rep. Bush said:

“The horrific circumstances surrounding the murder of Emmett Till have always been of great personal interest to me, particularly because Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till — a true and dedicated friend, a courageous civil rights leader in her own acts of commitment, and a particular asset to our nation’s children — was a longtime resident of the 1st Congressional District of Illinois, which also serves as Emmett’s final resting place. Last year, I called on Attorney General Jeff Sessions to reopen this case in light of new information that was revealed. I am glad to see the federal government following through on this request. This case is not only critically important for the role it played in sparking the Civil Rights movement, but so that Emmett and his family receive the justice that is owed to them. It is vital that everyone — both victims and perpetrators — knows that heinous crimes of this nature will never go unpunished… Emmett Till’s murder is a constant reminder of the violence and hatred espoused by a significant number of the majority for the African-American community. Even today, the crime that he was a victim of, lynching, is still not illegal under federal law. As recent events have shown, the vitriol and animus that existed in that era has not faded away. That is why I introduced H.R. 6086, a bill that would establish lynching as a criminal violation of the U.S. Code and I am glad to see that Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) has introduced the companion to my bill in the U.S. Senate… [I]ntolerance and animosity towards communities of color continue to plague our society. Without addressing the sins of our past, we will never achieve the understanding we need to truly achieve the reconciliation that will allow us to move forward.”

Lynching is the willful act of murder by a collection of people assembled with the intention of committing an act of violence upon any person. Historically, it’s been associated with racially-motivated crimes, especially in the South. From 1882 to 1968, nearly 5,000 people, over 70% of whom were African-American, were victims of lynching in the U.S. Despite the number of crimes, 99% of those responsible for lynchings escaped prosecution or punishment by state or local officials. According to a film produced by Ted Koppel, the last documented lynching in the U.S. was of Michael Donald in Mobile, AL in 1981 by two members of the KKK.

Congress has tried — and failed — to enact anti-lynching legislation at least 240 times. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, seven presidents called for an end to lynching, and the House of Representatives passed multiple anti-lynching measures between 1920 and 1940. The Senate, however, repeatedly failed to enact anti-lynching legislation despite repeated requests by civil rights groups, presidents, and the House of Representatives.

In 1918, Rep. Leonidas C. Dyer (R-MO) was the first to introduce an anti-lynching bill. His bill, intended to punish authorities that failed to prevent lynching, was designed to act as a deterrent that’d end the practice. Dyer’s bill ultimately died in the Senate after facing stiff opposition.

Media:

-

Sponsoring Rep. Bobby Rush (D-IL) Press Release

-

Sponsoring Rep. Bobby Rush (D-IL) Press Release on Emmett Till

-

LA Times (Context)

Summary by Lorelei Yang

(Photo Credit: iStockphoto.com / madsci)The Latest

-

Changes are almost here!It's almost time for Causes bold new look—and a bigger mission. We’ve reimagined the experience to better connect people with read more...

Changes are almost here!It's almost time for Causes bold new look—and a bigger mission. We’ve reimagined the experience to better connect people with read more... -

The Long Arc: Taking Action in Times of Change“Change does not roll in on the wheels of inevitability, but comes through continuous struggle.” Martin Luther King Jr. Today in read more... Advocacy

The Long Arc: Taking Action in Times of Change“Change does not roll in on the wheels of inevitability, but comes through continuous struggle.” Martin Luther King Jr. Today in read more... Advocacy -

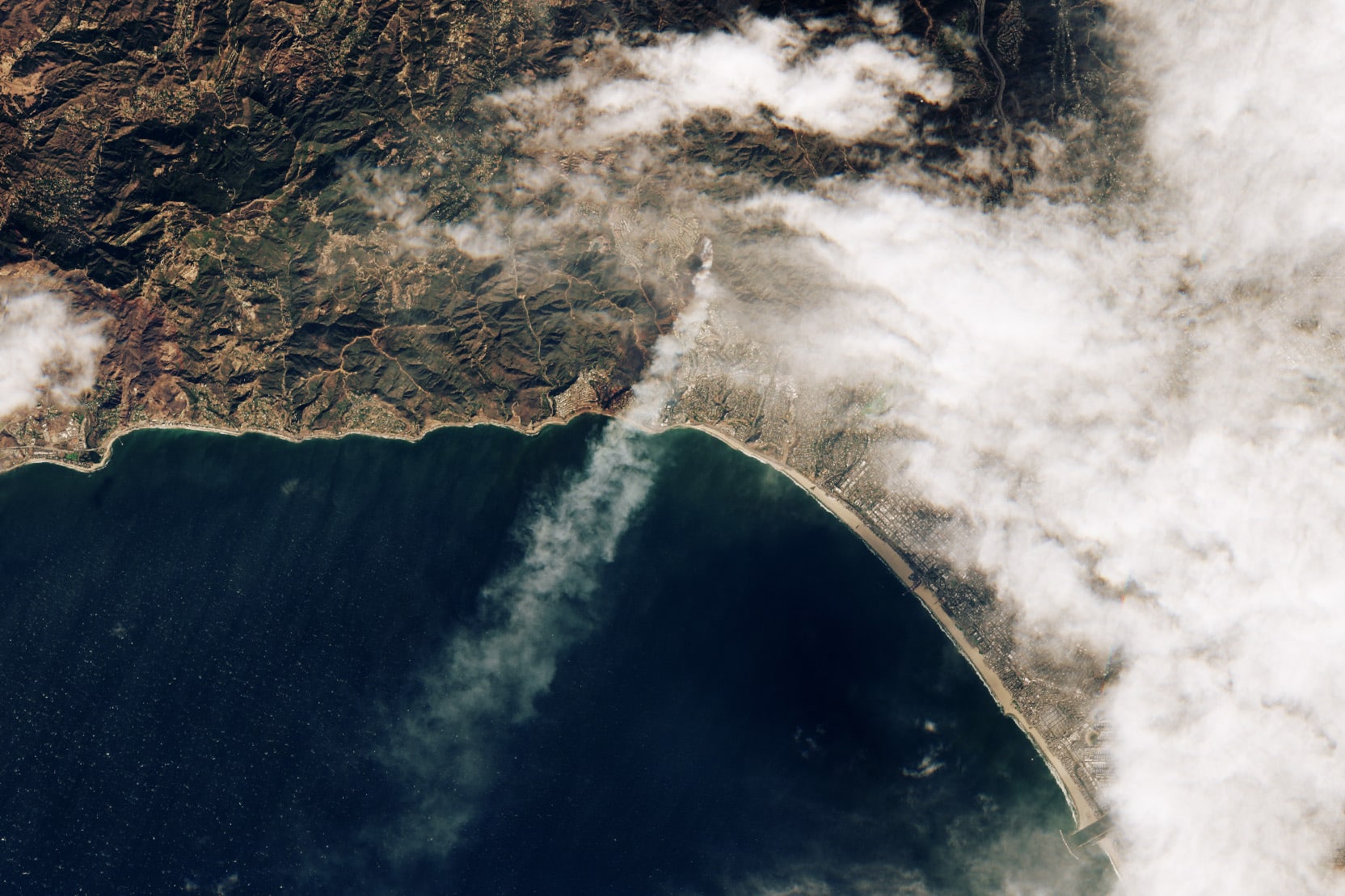

Thousands Displaced as Climate Change Fuels Wildfire Catastrophe in Los AngelesIt's been a week of unprecedented destruction in Los Angeles. So far the Palisades, Eaton and other fires have burned 35,000 read more... Environment

Thousands Displaced as Climate Change Fuels Wildfire Catastrophe in Los AngelesIt's been a week of unprecedented destruction in Los Angeles. So far the Palisades, Eaton and other fires have burned 35,000 read more... Environment -

Puberty, Privacy, and PolicyOn December 11, the Montana Supreme Court temporarily blocked SB99 , a law that sought to ban gender-affirming care for read more... Families

Puberty, Privacy, and PolicyOn December 11, the Montana Supreme Court temporarily blocked SB99 , a law that sought to ban gender-affirming care for read more... Families

Climate & Consumption

Climate & Consumption

Health & Hunger

Health & Hunger

Politics & Policy

Politics & Policy

Safety & Security

Safety & Security